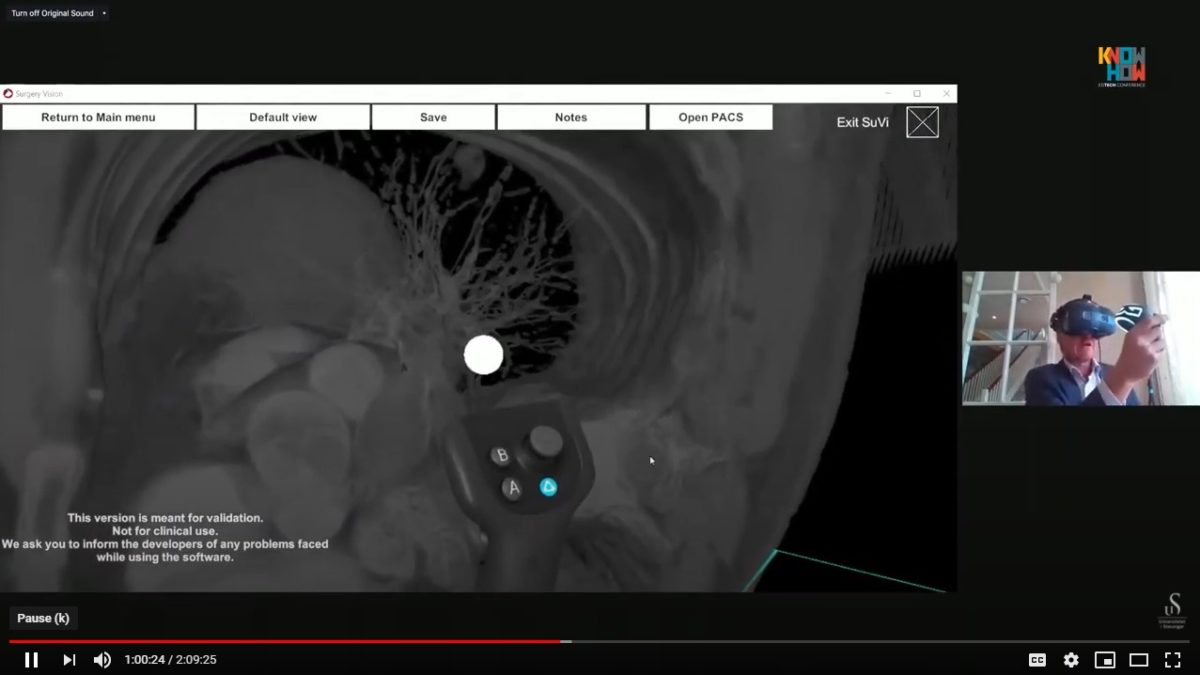

There are different technologies that can facilitate digital learning for health sciences students in an immersive environment, such as virtual reality (VR), simulation or 360° video amongst others. These environments allow the student to interact with a virtual world through their immersion in a three-dimensional context with real experiences.

Immersive learning is used in various disciplines outside of Health sciences including engineering, mathematics, education, biology, neuroscience, psychology, computer science, communication, economics and business. It enables interaction in multidimensional environments and provides valuable tools to improve practice and theory in order to enhance and promote transformational learning. So, it is not only about technology but also about designing activities using the technology for students to learn in context, therefore increasing knowledge and improving skills and competencies.

Mapping out the landscape

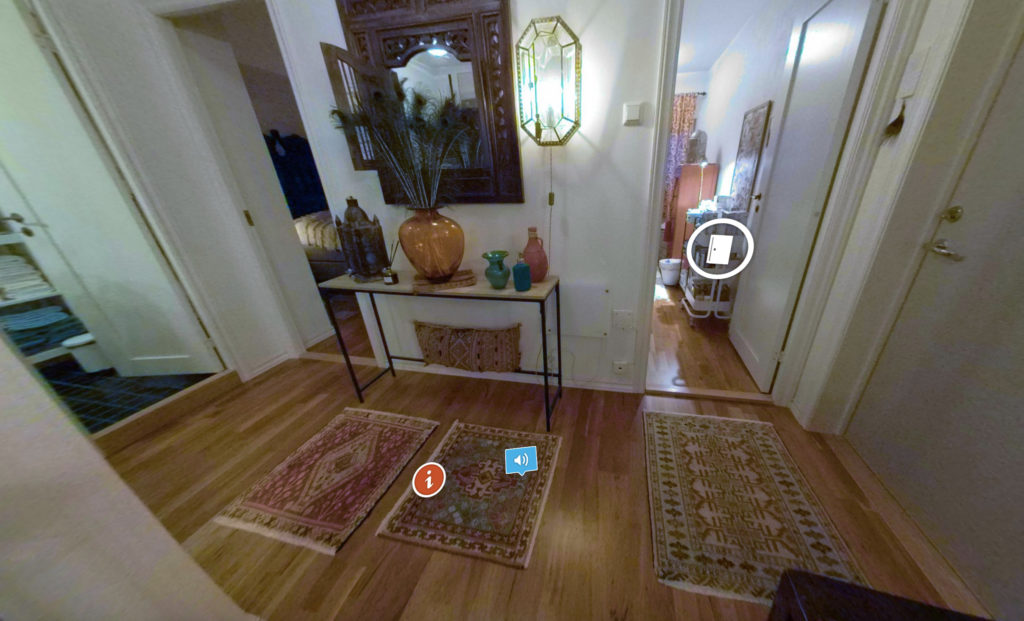

One of the work packages in the 360Visi project sets out to find out how and where 360° video simulation advantageously can be used in Health education.

The main objective of the study is:

- To identify specific proven areas in Health education where students will gain from 360° video simulation training.

In addition, the study has these specific objectives:

- To analyse whether new technologies like 360° video are effective tools for student learning

- To identify needs for 360° video simulation training at the universities participating in the project

Please note that this is a short description of the study and its findings. We will publish the entire study at a later stage.

Methods

The following approaches were used in the study:

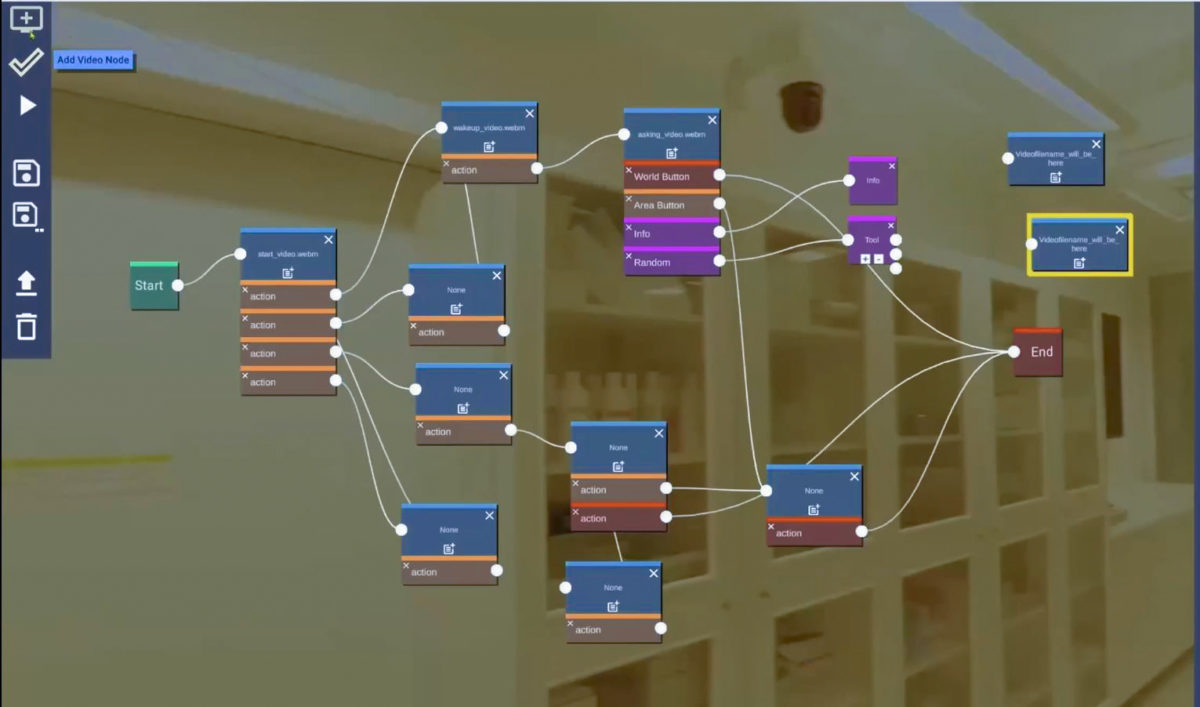

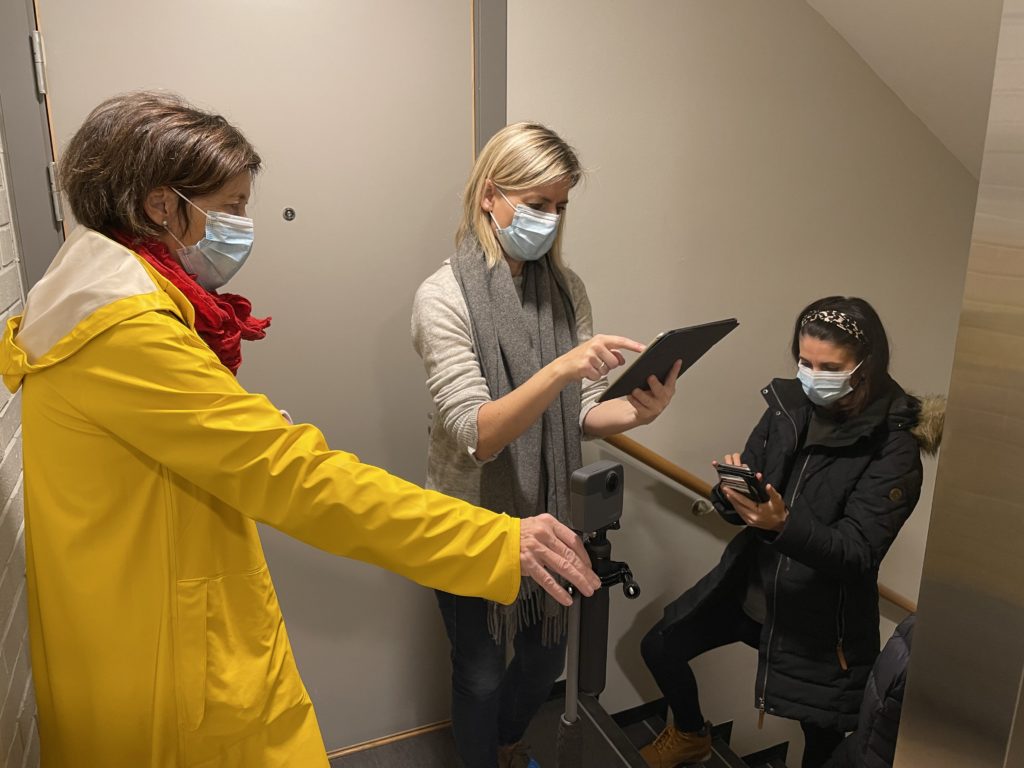

1.) Reviewing literature where simulation, 360° video, mobile phone applications, interactive video, telecare tools were used. The review included also 1b.) Information from the four universities participating in 360ViSi on their previous experience in the use of 360° video. Lastly 2.) A focus group of experts from each of the partner universities of the 360ViSi project, assessed the relevance, opportunity, effectiveness and feasibility of applying 360° technology in each of the areas of training in nursing education.

Literature review and previous experience

The evidence found from the literature review has shown that the use of new technologies in university teaching is already a reality that can benefit the learning of health sciences students. Specifically, the decrease in cost and the technological improvement on hardware in recent years have promoted the use of VR, AR or 360° video in this area of education.

The fact that students are able to have an experience before actual contact with a patient, either through real simulation or through virtual simulation, favours the consolidation of knowledge in a safer environment not only for the student but also the patient.

Of the four universities participating in the 360ViSi project, two of them have previous experiences with the use of 360° video technology in the teaching of health sciences students, and the other two universities had also developed technological solutions to improve the learning of their students.

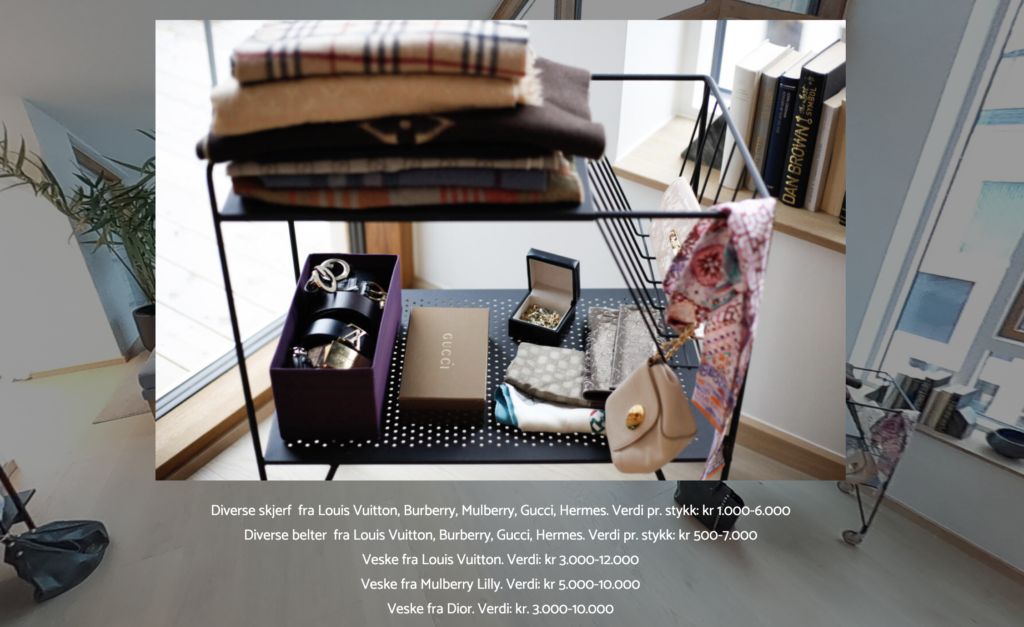

Six areas for enhanced learning

The experts from the four participating universities each identified areas where use of 360° video would be relevant in health education and gave them scores to show which were most relevant.

- Home care (Score 4)

- Nursing care and procedures (Score 4)

- Drug administration (Score 2)

- Surgical care (preoperative, perioperative, postoperative) (Score 2)

- Emergency and acute care (Score 3)

- Ethics and communication (Score 2)

The score corresponds to how many of the universities have chosen that area as a priority for the application of 360° video technology.

Within each of these areas, the experts found different items or competencies in which students could be trained using this technology and, also, enhance their learning. Each of them is detailed as follows:

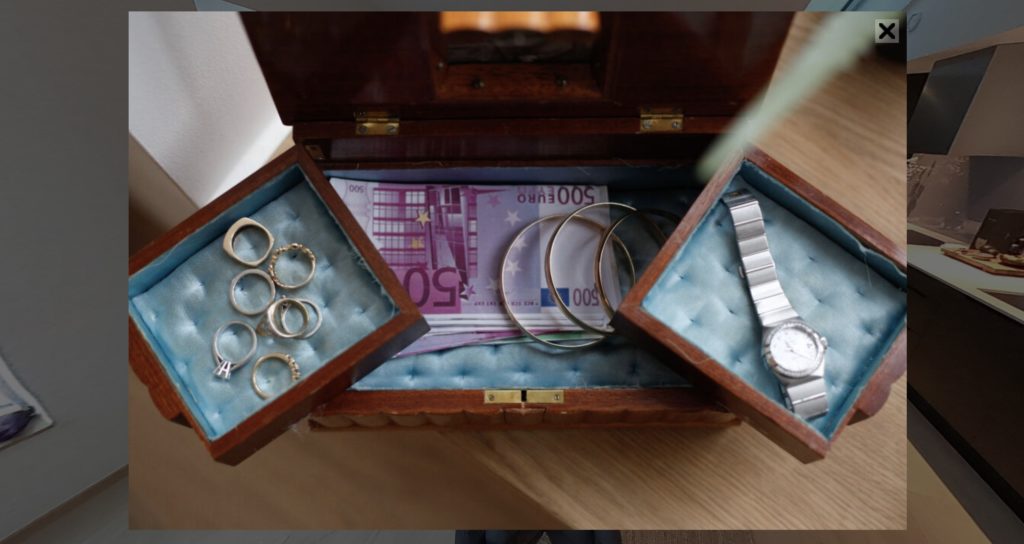

Home Care

The experts highlighted the need to work on Home Care, particularly with the elderly, paying special attention to care related to injuries caused by falls.

The possibility of working on correct decision-making in the patient’s home, especially in situations where there is palliative care involved in the home environment, was also underlined.

Another important aspect was the possibility of working on patient transfer (i.e. when transferring from/to their home and primary care or hospital facilities).

Nursing Care and Procedures

There is a mix of competencies that the experts have been emphasising, but they all have a point in common: the possibility for the student to acquire and incorporate practical skills and nursing care and procedures in a safe environment, through 360° technology, before their actual practice on real patients.

The need to enhance teamwork skills in nursing is emphasised, especially with the medical team during patient visits or ward rounds, which are necessary skills on all types of nursing care.

The importance of working on patient observation and clinical examinations of different kinds (assessment of the patient in pain, taking vital signs, knowledge of the clinical environment) has been highlighted by several universities.

Different techniques in the care of pediatric and adult patients, such as cannulation or the care and prevention of ulcers or wounds, was also pointed out.

Drug Administration

The experts emphasized the special benefit this technology could have for training in the work with drug administration – both for the administration of the medication, and also the organisation, drug preparation and drug round within the hospital environment.

360° technology can be a great tool for the student to effectively incorporate a systematic approach in their practice for the safe administration of medication.

Surgical Care (preoperative, perioperative, postoperative care)

Even though it has only been pointed out by the experts from two of the universities, care related to the surgical environment lends itself very effectively to learning through 360° technology, as studies analysed in the first phase also have shown.

The experts highlighted the need to apply the 360° technology on training in pre-operative care, anesthesia nursing care, assisting the surgeon during the operation, patient preparation and nursing care in trauma surgery.

Emergency and Acute Care

Three different areas have been identified within this item. Firstly, the need and importance of training on pre-hospital emergencies, given the property to rendering an image of the outdoors environment in 360° format enhances the teaching capacity in this area.

Secondly, hospital emergency/acute care, both in the emergency department and in the intensive care unit. Different needs were indicated in this field, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, care in patients with pulmonary oedema, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, etc. Thirdly, the expert group also sees possibilities for learning about the care of the ventilated patient, both on the use of ventilators and on techniques related to aspiration of secretions as an example.

Ethics and Communication

The experts from two universities pointed out the suitability of the 360° video technology in the area of Ethics and Communication. Specifically, the possibility of training on breaking bad news was highlighted, as well as the holistic assessment of the patient, evaluating their needs in full, taking into account patient beliefs, diversity and cultural aspects. Communication and correct decision-making can also be skills to be acquired effectively through the use of 360° video.

Reinforcing learning and training with minimal risk

360 video and other immersive technologies has unique features that allow the user to train at their discretion in a safe and non-intrusive environment.

It is clear that there is unanimous belief among the experts from the participating universities in the 360ViSi project that certain areas of learning can be reinforced by 360° video technology in order to help students consolidate high standards in nursing care and health education.

The methods that bring the student closer to their future professional role, and in which they can learn by repetition, and correct mistakes as many times as they need with minimal risk, should become increasingly important in the teaching-learning process. Beyond that, 360° video technology will in an academic university environment still require teaching and supervision in real time and in groups. This is also a context where the technology can be explored for new ways of learning – where the instructor can control what students look at, to make them aware of and reflect on certain details, ask them questions or correct common mistakes.

Please note that this is a short description of the study and its findings. We will publish the entire study at a later stage.

Literature

Literature reviewed and applied in the full 360ViSi project study and analysis of Needs for simulation tools in Health Education:

- Ayala Pezzutti, R.J., Laurente Cárdenas, C.M., Escuza Mesías, C.D., Núñez Lira, L.A., Díaz Dumont, J.R., Ayala Pezzutti, R.J., et al. (2020). Mundos virtuales y el aprendizaje inmersivo en educación superior. Propósitos y Represent. 8(1).

- Kilmon, C.A., Brown, L., Ghosh, S., Mikitiuk, A. (2010). Immersive virtual reality simulations in nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect. 31(5):314-317.

- Kinio, A., Dufresne, L., Brandys, T., Jetty, P. (2017). Break Out of the Classroom: The Use of Escape Rooms as an Alternative Learning Strategy forSurgical Education. J Vasc Surg. 66(3):e76.

- Akhtar, K., Sugand, K., Sperrin, M., Cobb, J., Standfield, N., Gupte, C. (2015). Training safer orthopedic surgeons. Acta Orthop. 3 de septiembre de. 86(5):616-21.

- Harris, D.J., Bird, J.M., Smart, P.A., Wilson, M.R., Vine, S.J. (2020). Un marco para la prueba y validación de entornos simulados en experimentación y entrenamiento. Fronteras en psicología, 11, 605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00605

- Jensen, L., & Konradsen, F. (2018). A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Education and Information Technologies, 23(4), 1515-1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017- 9676-0

- Falconer, C.J., Slater, M., Rovira, A., King, J.A., Gilbert, P., Antley, A., Brewin, C.R. (2014). Embodying compassion:

a virtual reality paradigm for overcoming excessive selfcriticism. PLoS One. 9, 11, e111933

- Tropea, Joanne & Johnson, Christina & Nestel, Debra & Paul, Sanjoy & Brand, Caroline & Hutchinson, Anastasia & Bicknell, Ross & Lim, Wen. (2019). A screen-based simulation training program to improve palliative care of people with advanced dementia living in residential aged care facilities and reduce hospital transfers: study protocol for the Improving Palliative care Education and Training Using Simulation in Dementia (IMPETUS-D) cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Palliative Care. 18. 10.1186/s12904-019-0474-x.

- Hanson, J., Andersen, P., Dunn, P.K. (2019). Effectiveness of three-dimensional visualisation on undergraduate nursing and midwifery students’ knowledge and achievement in pharmacology: A mixed methods study. Nurse Educ Today. 81:19-25. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.06.008

- Green, J., Wyllie, A., & Jackson, D. (2014). Virtual worlds: a new frontier for nurse education? Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia), 21(2), 135–141. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25109212

- Tjoflåt, I., Brandeggen, T. K., Strandberg, E. S., Dyrstad, D. N., & Husebø, S. E. (2018). Norwegian nursing students’ evaluation of vSim® for Nursing. Advances in Simulation. 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-018-0070-9

- Harrington, C. M., Kavanagh, D. O., Wright Ballester, G., Wright Ballester, A., Dicker, P., Traynor, O., Tierney, S. (2018). 360° Operative Videos: A Randomised Cross- Over Study Evaluating Attentiveness and Information Retention. Journal of Surgical

Education. 75(4), 993–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.10.010

- Watson, W., & Yang, S. (2016). Games in schools: Teachers’ perceptions of barriers to game-based learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research. 27(2), 153-170

- Yi-Lien, Y., Yu-Ju, L., & Yen-Ting, R. L. (2018). Gender-Related Differences in Collaborative Learning in a 3D Virtual Reality Environment by Elementary School Students. Educational Technology & Society, 21(4), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.2307/26511549

- Choi, K. S. (2017). Virtual reality in nursing: Nasogastric tube placement training simulator. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 245, 1298. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-830-3-1298.

- Hernández-Sampieri, R., Baptista-Lucio, P. & Fernández-Collado, C. (2010). Metodología de la investigación (5ta ed.). México: McGraw Hill.

- Szyld, D., Uquillas, K., Kalet, A. (2017). Improving the clinical skills performance of graduating medical students using “WISE OnCall,” a multimedia educational module. Simulation in Healthcare. 12, 385–392. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000254

- Khan, R., Plahouras, J., Johnston, B.C., Scaffidi, M.A., Grover, S.C., Walsh, C.M. (2018). Virtual reality simulation training for health professions trainees in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Vol. 2018, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2018.

- Pires, S., Monteiro, S., Pereira, A., Chaló, D., Melo, E., Rodrigues, A. (2017). Non-technical skills assessment for prelicensure nursing students: An integrative review. Vol. 58, Nurse Education Today. Churchill Livingstone; 2017. p. 19–24.

- Alfalah, S.F.M., Falah, J.F.M., Alfalah, T. et al. (2019). A comparative study between a virtual reality heart anatomy system and traditional medical teaching modalities. Virtual Reality 23, 229–234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-018-0359-y

- Kamińska, D.; Sapiński, T.; Wiak, S.; Tikk, T.; Haamer, R.E.; Avots, E.; Helmi, A.; Ozcinar, C.; Anbarjafari, G. (2019). Virtual Reality and Its Applications in Education: Survey. Information 2019, 10, 318. doi:10.3390/info10100318

- Shanahan, M. (2016). Student perspective on using a virtual radiography simulation Radiography, Volume 22, Issue 3, 217 – 222 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2016.02.004

- McDowell, J., Styles, K., Sewell, K., Trinder, P., Marriott, J., Maher, S., & Naidu, S. (2016). A Simulated Learning Environment for Teaching Medicine Dispensing Skills. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 80(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe80111

- Jeffrey Woo, M., Andrew Newman, S. (2020). The experience of transition from nursing students to newly graduated registered nurses in Singapore. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 1 (7). 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.11.002

- González Izard, S., Juanes Méndez, J., García-Peñalvo, F., Jiménez López, M., Pastor Vázquez, F. & Ruisoto, P. (2017). 360° vision applications for medical training. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM 2017). Association for Computing Machinery. New York, NY, USA, Article 55, 1–7. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3144826.3145405

- Jessalyn, I. V., Kaufmann, R., Brandi, N. F. & Joe, C. M. (2020). Technology acceptance model: investigating students’ intentions toward adoption of immersive 360° videos for public speaking rehearsals, Communication Education, DOI: 10.1080/03634523.2020.1791351

- Taubert, M., Webber, L., Hamilton, T., Carr, M., & Harvey, M. (2019). Virtual reality videos used in undergraduate palliative and oncology medical teaching: results of a pilot study. BMJ supportive & palliative care. 9(3), 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001720

- Herault, R. C., Lincke, A., Milrad, M., Forsgärde, E.-S., Elmqvist, C., & Svensson, A. (2018). Design and Evaluation of a 360 Degrees Interactive Video System to Support Collaborative Training for Nursing Students in Patient Trauma Treatment. In 26TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTERS IN EDUCATION (ICCE 2018). (pp. 298–303). Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education.

- Molka-Danielsen, J., Prasolova-Førland, E., Fominykh, M. & Lamb, K. (2018). “Use of a Collaborative Virtual Reality Simulation for Multi-Professional Training in Emergency Management Communications,” 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE), Wollongong, NSW, 2018, pp. 408-415, doi: 10.1109/TALE.2018.8615147.

- Matthews, T.J., Tian, F., Dolby, T. Interaction design for paediatric emergency VR training. Virtual Reality & Intelligent Hardware. 4 (2). 330-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vrih.2020.07.006

- Donnelly, F., McLiesh, P., Bessell, S. (2020). Using 360° Video to Enable Affective Learning in Nursing Education. Journal of Nursing Education. 59(7):409-412 https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200617-11

- Jefferies, D., McNally, S., Roberts, K., Wallace, A., Stunden, A., D’Souza, S., Glew, P. (2018). The importance of academic literacy for undergraduate nursing students and its relationship to future professional clinical practice: A systematic review, Nurse Education Today, 60. 84-91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.020.

- Sá, M.J., Serpa, S. (2018). Transversal Competences: Their Importance and Learning Processes by Higher Education Students. Educ. Sci. 8, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030126

- Caena, F. (2019) Developing a European Framework for the Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence (LifEComp) , Punie, Y. editor(s), EUR 29855 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, , ISBN 978-92-76-11225-9 (online), doi:10.2760/172528.

- Tracy, G., DeCristofaro, C. (2016). Use of Smartphones With Undergraduate Nursing Students. Journal of Nursing Education. 2019;55(7):411-415. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20160615-11

- Smeltzer, S., Ross, J., Mariani, B., Meakim, C., Bruderle, E., Petit de Mange, E., Nthenge, S. (2018). Journal of Nursing Education. 2018;57(12):760-764 https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20181119-11

- Gomes, A. T. d. L., Salvador, P., Goulart, C. F., Cecilio, S. G., & Bethony, M. F. G. (2020). Innovative methodologies to teach patient safety in undergraduate nursing: Scoping review. Aquichan, 20(1), 1-14. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2020.20.1.8

- Cant, R., Cooper, S. (2017). The value of simulation-based learning in pre-licensure nurse education: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Nurse Education in Practice. 27. 45-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.08.012