Evaluating Accessibility of 360-Degree Video

By Michael Taylor, Learning Technologist and Project Developer, University of Nottinghan.

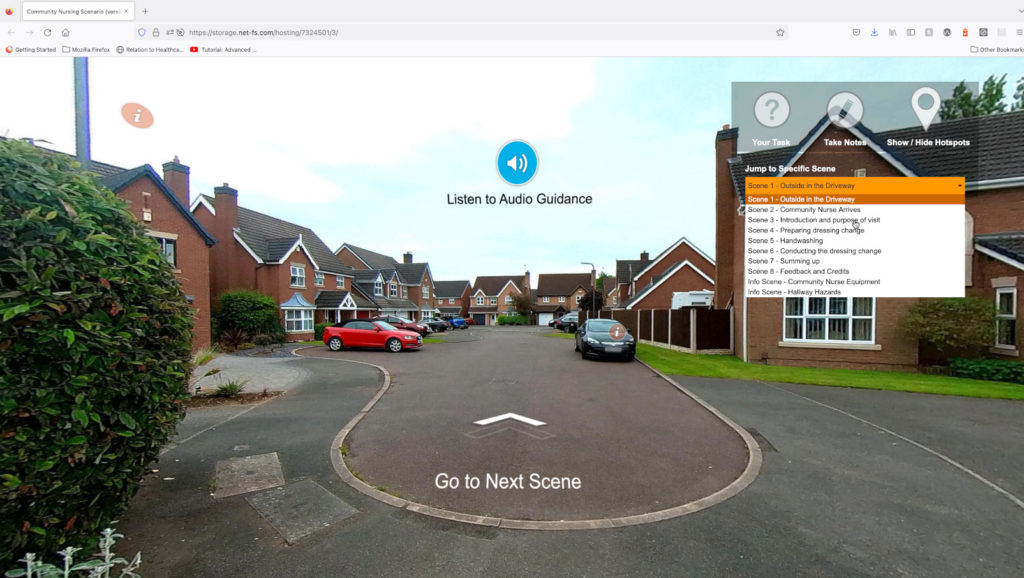

The goal was to understand if the video met current Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WGAC 2.1) for users with disabilities and if there was a need for developing a supplementary compliant HTML based version of the home visit. The decision to develop a second resource was based on the team’s research findings. The evaluation was supported by consulting with immersive accessibility experts working in UK academia.

Methods

The evaluation team held interviews with two Nottingham University students who had disabilities. One had a physical impairment and the other had neurological differences.

The students were asked:

- for their general thoughts on working with the 360 resource?

- how accessible was the secondary HTML resource compared to the 360-video?

- which resource they thought was most useful for learning and why?

During 90-minute sessions, the students used think-aloud methodology to provide feedback while interacting with both the 360-degree and HTML resources. Researchers observed and recorded the session whilst taking notes.

The sessions also focused on the four key WGAC 2.1 requirements: compatibility with assistive technology, keyboard navigation/controls, captions/transcripts and audio descriptions.

After providing feedback on both resources the students were asked to complete a Fokides & Arvaniti accessibility questionnaire.

Key Findings

- Both students found the 360-degree video immersive and realistic but had issues with lack of pause feature and small interface elements.

- The HTML secondary version provided clearer expectations and objectives. Both participants commenting that its interactive elements were easier to use.

- Students were unfamiliar with accessibility features like audio descriptions. This likely contributed to lack of feedback in those areas.

- Although the HTML secondary resource did fully meet WGAC 2.1 accessibility standards. It raised further questions around the overhead in terms of time and expense in providing a secondary resource. This aligns with the broader challenges in making 360-degree video accessible.

Recommendations

- Consider accessibility early in 360-degree video development, not as an afterthought. Research tools thoroughly.

- Current off-the-shelf tools may not allow full WCAG 2.1 compliance. Additional resources may be needed, despite added time and cost.

- Help educate users on accessibility features in 360-degree video. Lack of awareness poses a barrier.

- Conduct further outreach to users with diverse disabilities during evaluation. Sample size was a limitation of this study.

Conclusion

While 360-degree video offers rich educational experiences, more work is needed to make it inclusive for all learners. Accessibility must be a priority from the outset when developing immersive media tools and content.